“Preparing and delivering a performance assessment is one of the hardest tasks you’ll have to perform as a manager.” – Andy S. Grove, High Output Management

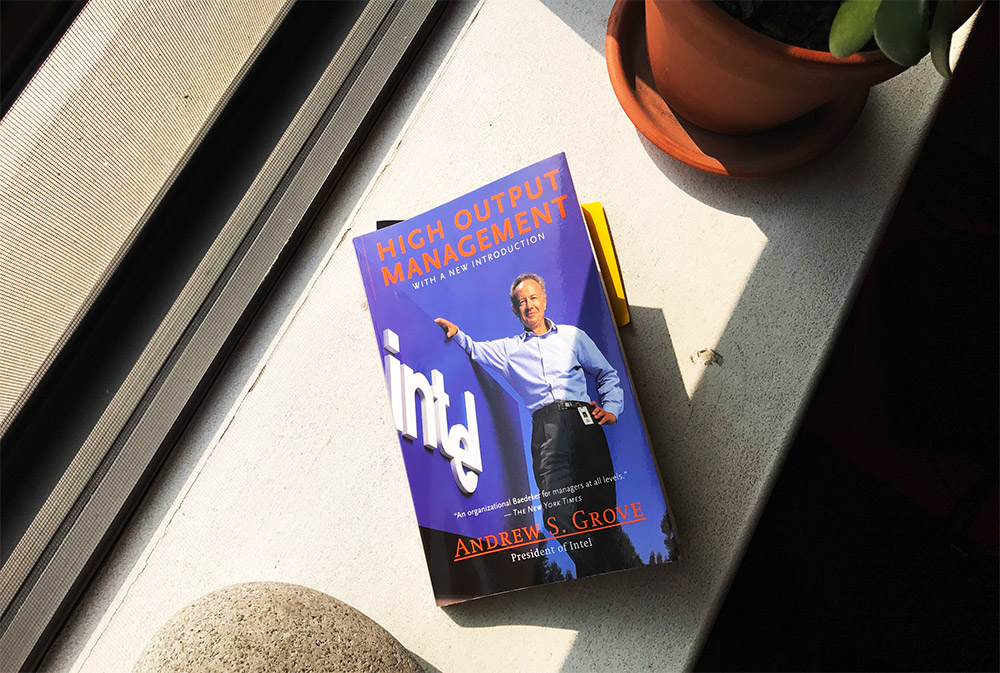

I’ve been re-reading sections of High Output Management by Andy Grove of Intel fame (he was president and then CEO at Intel during its years of incredible growth; Grove passed away in March 2016). There are a lot of valuable nuggets throughout the book. I wanted to highlight a section from his chapter “Performance Appraisal: Manager as Judge and Jury” because I thought it would serve as a great reminder for myself whenever I have to engage in performance reviews of employees at work. Grove introduces what he calls the “three L’s” to keep in mind when delivering performance reviews:

- Level: be honest and straightforward in giving both praise and criticism to the employee

- Listen: employ all your senses to make sure that the employee has fully understood what you are trying to communicate; in addition to using words, be sure to watch how the employee receives and reacts to the messages, and keep at it until you’re sure the employee is on the same page

- Leave yourself out: giving performance reviews is tough and can bring out emotions in not only the employee but you as the reviewer; control your emotions and focus on the fact that the review is all about the employee and his/her performance

The section is called “Deliver the Assessment” and here’s basically the full text:

There are three L’s to keep in mind when delivering a review: Level, listen, and leave yourself out.

You must level with your subordinate–the credibility and integrity of the entire system depend on your being totally frank. And don’t be surprised to find that praising someone in a straightforward fashion can be just as hard as criticizing him without embarrassment.

The word “listen” has special meaning here. The aim of communication is to transmit thoughts from the brain of person A to the brain of person B. Thoughts in the head of A are first converted into words, which are enunciated and via sound waves reach the ear of B; as nerve impulses they travel to his brain, where they are transformed back into thoughts and presumably kept. Should person A use a tape recorder to confirm the words used in the review? The answer is an emphatic no. Words themselves are nothing but a means; getting the right thought communicated is the end. Perhaps B has become so emotional that he can’t understand something that would be perfectly clear to anyone else. Perhaps B has become so preoccupied trying to formulate answers he can’t really listen and get A’s message. Perhaps B has tuned out and as a defense is thinking of going fishing. All of these possibilities can and do occur, and all the more so when A’s message is laden with conflict.

How then can you be sure you are being truly heard? What techniques can you employ? Is it enough to have your subordinate paraphrase your words? I don’t think so. What you must do is employ all of your sensory capabilities. To make sure you’re being heard, you should watch the person you are talking to. Remember, the more complex the issue, the more prone communication is to being lost. Does your subordinate give appropriate responses to what you are saying? Does he allow himself to receive your message? If his responses–verbal and nonverbal–do not completely assure you that what you’ve said has gotten through, it is your responsibility to keep at it until you are satisfied that you have been heard and understood.

This is what I mean by listening: employing your entire arsenal of sensory capabilities to make certain your points are being properly interpreted by your subordinate’s brain. All the intelligence and good faith used to prepare your review will produce nothing unless this occurs. Your tool, to say it again, is total listening.

Every good classroom teacher works in the same way. He knows when what he is saying is being understood by his students. If it isn’t, he takes heed and explains things or explains things in a different way. All of us have had professors who lectured by looking at the blackboard, mumbling to it, and carefully avoiding direct eye contact with the class. The reason: knowing that their presentation was murky and incomprehensible, these teachers looked away from their audience to avoid confirming visually what they already knew. So don’t imitate your worst professors while delivering performance reviews. Listen with all your might to make sure your subordinate is receiving your message, and don’t stop delivering it until you are satisfied that he is.

The third L is “leave yourself out.” It is very important for you to understand that the performance review is about and for your subordinate. So your own insecurities, anxieties, guilt, or whatever should be kept out of it. At issue are the subordinate’s problems, not the supervisor’s, and it is the subordinate’s day in court. Anyone called upon to assess the performance of another person is likely to have strong emotions before and during the review, just as actors have stage fright. You should work to control these emotions so that they don’t affect your task, though they will well up no matter how many reviews you’ve given.

I’ve given over 100 performance reviews during my years at Barrel. We’ve made many tweaks to the format over the years, and yet, I know there’s still room for improvement. Looking back, the best reviews are those that have had proper preparation, solid documentation, and a session in which I was able to follow through on the 3 L’s–I gave frank, straightforward praises and critiques; the “listening” was evident in a productive communication flow; and I was able to avoid making any of part of the discussion about myself, keeping the focus totally on the employee. The challenge for myself and our organization is to raise the quality and consistency of our reviews so that even during very busy times, we are able to provide our team members with helpful and productive performance assessments that not only look back on their past work but help them chart the course for substantial improvements in the following weeks and months.